Washington Warned: Illuminati Infiltrating American Revolution

A letter from our nation’s first president and commander general of the American Revolutionary War written in 1798 affirms that he knew the Illuminati, based in Europe, had arrived on American shores.

The revolution — which began with uproar over the Stamp Act in 1765, led to the Boston Tea Party in 1773, solidified in the first battle at Lexington & Concord in 1775, then took shape via a bold Declaration of Independence in 1776, and which continued through a long, exhausting campaign of endurance against history’s most powerful empire — did not end with decisive victory at Yorktown in 1781.

Nor did it end with the completion of the Constitution after extensive deliberations at the conventions, as the battle for the Bill of Rights and ratification not only continued the debate but complicated it with important questions about the nature of government, and the limitations that should be put upon it. Rather than concluding with the ratification of the Constitution (with the added, demanded Bill of Rights) in 1791 by the several States, this struggle continued through the faction fights of the Federalists, the Anti-Federalists and the Democrat-Republicans.

As president, Washington tried to remain neutral to these disputes in his official capacity and public persona, though in reality he was more closely aligned with the Federalists and stacked figures like Alexander Hamilton in his cabinet. Thomas Jefferson, who led the Democrat-Republican Party, backed in turn by the Democratic Societies, was scrutinized by many in the founding era for his personal beliefs and relationship with conspiratorial European elements. Washington’s response about the Illuminati’s influence in America followed the significant uproar caused by the printing and circulation of John Robison’s Proofs of a Conspiracy (Against All the Religions and Governments of Europe Carried on in the Secret Meetings of Freemasons, Illuminati and Reading Societies) in 1798.

This work was propagated in particular by geographer and pastor Jedidiah Morse, especially in Massachusetts and the other Northern States where it gripped the Protestant, Federalist circles there who had grown to view Jefferson and his ilk as nefarious figures working against the America they had fought to create, and who they believed to be involved with the odious tenets of the French Revolution and the Illuminati organization that had perpetrated it.

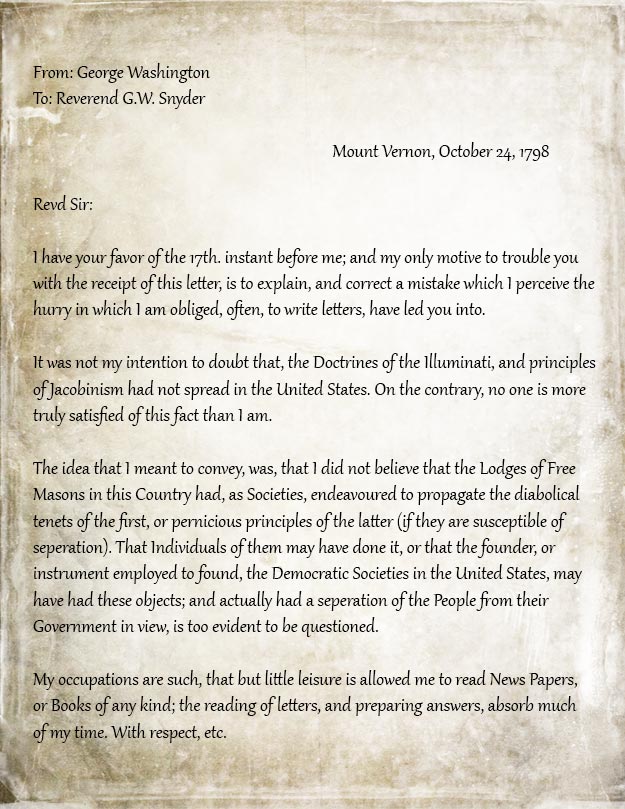

It is in this important context that George Washington wrote the letter below, approximately a year and a half before his death in December of 1799, not to dispel rumors of the Illuminati and its presence in America. Instead, Washington meant to clarify that the Illuminati was not carried in the Halls of Masonry at large, but in the circles of the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican (secret) Societies who strongly opposed the Federalists in control of the government.

The letter reads:

About a year and a half before his death, George Washington issued a letter confirming that the doctrines of the Illuminati and principles of Jacobinism had indeed spread; not through Freemasonry as some believed, but instead through the Jefferson-linked Democrat-Republican Societies who deeply opposed the Federalists.

This revolution was different, and set apart at a minimum from other revolutions that inevitably soured with the usurpation of power by dictators who either helped lead the revolution or came to power on its heels by the fact that it resisted the forces that would establish a dictator, king or other form of autocratic rule.

Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely, so said Lord Acton. The American Revolution fortunately did not become a historical case of absolute tyranny, yet there were many important struggles for power among the many factions and key leaders of early America, and indeed it was rife with conspiracy, subterfuge and plain old corruption.

Illuminati Manifesto of World Revolution by Marco de Luchetti, technically a forward to conspirator of the French Revolution Nicholas Bonneville’s 1792 book L’Esprit Des Religions, explains how the French secret society/publisher Le Cercle Social housed the key French members of the Bavarian Illuminati who carried out a definite conspiracy via the French Revolution. Included among the key backers of this Illuminati conspiracy are the Rothschild family, who bankrolled founder Adam Weishaupt, the Saxe-Gotha family who protected Weishaupt after the secret group was exposed, as well as the Marquis de Lafayette, who served as a general in the American Revolution and as a leader of the Garde Nationale in the French Revolution.

The French branch of the Illuminati comprised a distinct faction inside the Jacobins via a political cadre generally referred to as the Girondins; this group was later overpowerd by the Montagnards (also Jacobins), as detailed at length by Luchetti. He argues that under the leadership of Robespierre, they took over and bloodied the revolution already underway, carrying out not only the executions of thousands of aristocrats and clergy members, but exacting also a larger depopulation effort, particularly among the plebiscites.

Luchetti documents how an effort had been declared to wipe out 2/3 of all of France, aiming to eradicate some 16 million people from the nearly 25 million who comprised France’s population at the time. From page 337:

Two thirds of the citizens are villains: the enemies of liberty. They ought to be exterminated. Terror is the Supreme Law. It is the instrument to aid us. It is an object of veneration. Destruction must be constantly the order of the day. If the sword ceases to operate, if the executioners do not serve as fathers of their country, liberty is at risk. It wants to reign over a pile of cadavers, watered by the blood of its enemies.

This macabre effort was underway, resulting in more than a million dead through starvation (the food supply was artificially constrained and centralized), fire, famine and the sword. It ended only when Robespierre’s dark revolution was overthrown and he was executed without trial via the same guillotines he had been using to carry out his terror.

Not surprisingly, after the Cercle Social played such a crucial role in overthrowing the existing order and seizing power, many of the French Illuminists who had opposed Robespierre from within the Jacobins were arrested and or executed under Robespierre’s reign.

Among these was the British-born Thomas Paine, closely connected occultically to illuminist-extraordinaire Benjamin Franklin.

Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense, published in January 1776, sparked revolution in the general population, while arguing decisively for a declaration of independence from Britain and a commitment to resistance at any price. His 1791 book Rights of Man coincided with his campaign to support the French Revolution, taking residence there for many years under an honorary grant of citizenship while fomenting designs for worldwide revolution. By 1793, after years of extremely close work with Nicholas Bonneville, the publisher at the heart of the Cercle Social secret society, Paine was regarded as an enemy of the Montagnards, arrested and left to await execution at the guillotine. During his imprisonment, he wrote The Age of Reason, which advocated an order based around the destruction of all established religions and the deification of Reason.

During this time, Paine appealed to Gouverneur Morris, then ambassador to France, as well as to President Washington to intervene to save his life; however, no support was offered, leading Paine to bitterly blame both men as conspirators aiding Robespierre in arresting him. Thomas Paine attacked Washington in particular, blasting him as a ‘treacherous man unworthy of his fame as a military and political hero,’ and questioned his principles in a 1796 letter that referred to him, in part, as an imposter.

In all likelihood, George Washington refused to intervene due to his knowledge of Paine’s involvement in the Illuminati and his hand in the French Revolution, which had embarrassed the many Americans who had supported it as a reciprocation for their aid in the American Revolution, but which had turned needlessly dark and bloody.

Both Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson became heavily involved with, and tied to, the secret societies of France and Europe at large during their extensive time there as ambassadors prior to the French Revolution. Jefferson is on record as supporting the expressed aims of Adam Weishaupt, and his vision for the perfectibility of man, while he incorporated many esoteric thematics connotating an illuminated status into his Monticello estate, which grew to include 33 rooms and bore various symbolic architectural elements. Jefferson, accused of being an atheist by many at the time, was at the center of the era’s tense partisanship and hotly opposed by many as an agent of subterfuge and subversive to establishment government (largely directed by Federalism until his presidency).

The revolutionary government of France encouraged support from America in its war against Britain in 1793. Its diplomat Edmond-Charles Genet came to America to propagandize ‘democratic support against aristocratic tendencies,’ leading to the formation of Democratic Societies (also Democratic-Republican Societies) who supported the effort in France and opposed the Federalists at home, whom they saw as masquerading for aristocratic and/or centralized rule. President Washington denounced the Democratic Societies in his annual address to Congress in 1794, mistrustful of the factions he saw as too closely tied to revolutionary France.

Opposition to these societies was based around the widespread belief that their tactics in opposing leaders in office amounted to seditious behavior, sparking wider debate about the extent to which the freedom of speech, press and assembly extend. It set the stage for the Alien and Sedition Acts that became draconian law under President John Adams in 1798 that essentially limited civil rights and led to the imprisonment of journalists and suspected spies.

Who was the American Revolution really for? Who really won that revolution? And who does it serve now? What is the proper role of government in our lives, and what has it transformed into today?

The Bill of Rights and Constitution clearly establish bedrock principles to establish a free society upon — and establish limitations over — government, but the other answers don’t come so easily.

Were the elements of the Illuminati in America ultimately malevolent? Or did they do some good? Certainly secrecy and subterfuge don’t tend to breed good government. Yet many of the members of the Democrat-Republican Societies and the Jefferson revolution joined to oppose the powers given to government under Federalist design and execution, and favored strong States rights like other anti-Federalist factions.

Is it one side or the other who represents true freedom? Or are they both factions tainted by corruption and the real politics of the day?

Clearly the French Revolution went too far, but to what extent was the American Revolution ever fulfilled? Did the United States of America ever embody the dream of its founders, and if so, do we have any of it left, still intact today?